I Remember You

This project formed Stuart's first exhibition at The Riflemaker Gallery in London 2010.

I REMEMBER YOU

by Stuart Pearson Wright

If one thing persists in my thoughts after making this series of work: the paintings, drawings, the songs I’ve recorded and the film installation Maze, it is principally the necessity to laugh at oneself: at one’s vanity, follies and fears. I realised, in contemplating the reasons for making this work, the importance of being able to examine one's own identity without taking oneself too seriously. Artists do take themselves seriously, the whole time. They are so bloody earnest. However I think that it's possible to delve deeply into the pits of one's worst existential anxieties and dig up a great deal of mirth. It’s something I think that Samuel Beckett did very successfully. In a round about way I believe that's what I am trying to do, in everything that I make.

There is light at the end of the proverbial tunnel if one can only take a step back from one’s anxieties and see the comedy that lies within one’s own morbid feelings.

“I HAVE A FACE, BUT A FACE IS NOT WHAT I AM”

Julian Bell, ‘Five Hundred Portraits’ (Phaidon) 2001

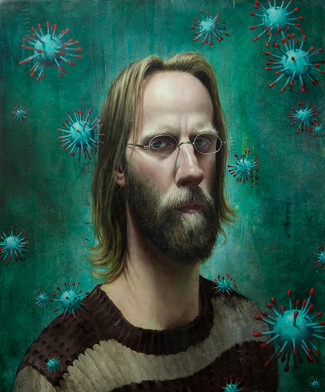

The work of Stuart Pearson Wright (b. Northampton 1975) reflects a search for lost identity. One of the first children born in the UK by artificial insemination the artist feels that the process has created an ‘identity void’ which his work attempts to confront. Wright’s new series of paintings at Riflemaker - shown alongside a film installation featuring Keira Knightley - explore and dispel the stereotypes of masculinity and femininity as depicted in films, books and comics; specifically in the stories and myths of the American West.

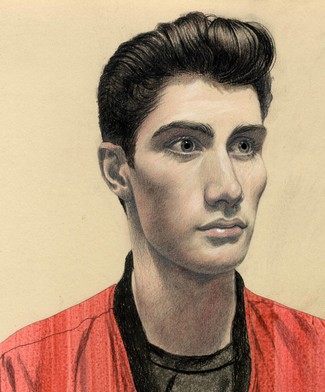

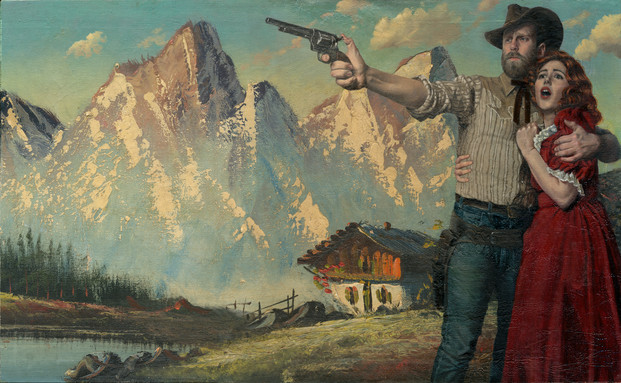

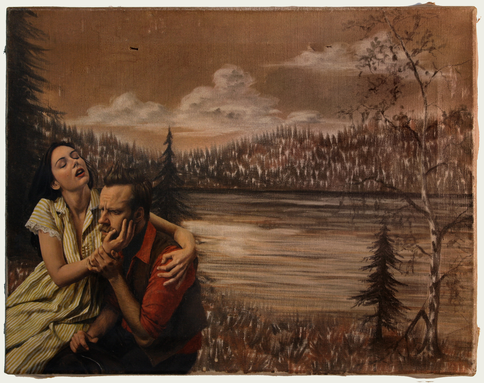

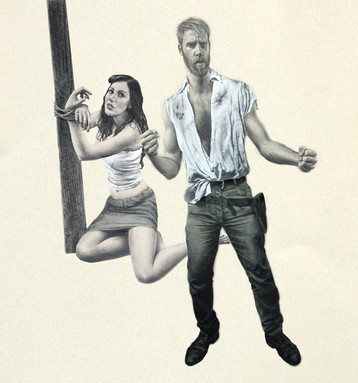

Choosing to paint the human figure in an era when it was not always seen as a legitimate part of contemporary art, and a winner of the BP Portrait Award aged just 26, Wright has spent much of his career attempting to subvert traditional portrait painting. He distorts his subjects, employing his own features and those of his fiancée in meticulously painted and stylised characters set in pulpy, fictional situations.

Having never met his father, Wright says: ‘Each time I paint my own face I am looking at the face of my father - without knowing who he is or was or what he looked like. As a result, I'm interested in the ways in which we construct ourselves and our apparent identities - and the layers and the processes we go through in that construction’.

In the double-screen film installation, ‘Maze’, written and directed by the artist, Wright and Knightley play Elizabethan courtiers lost in a grand maze. Only a hedge separates the frustrated and rather lacklustre pair. They hear each other’s cries but are unable to locate one another. Eventually it is the man who fails to rescue his lover while the woman regains composure, the work being a metaphor for a relationship breaking down.

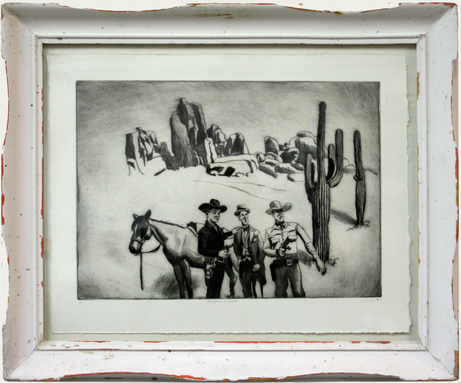

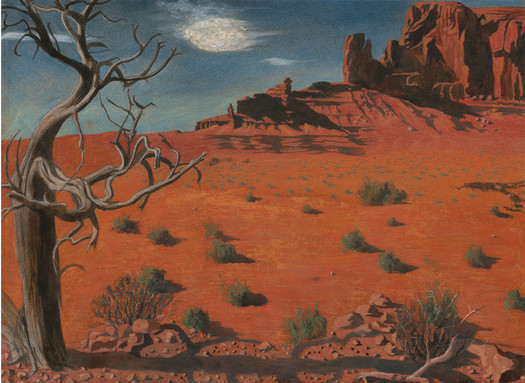

The cowboy as an archetypal masculine hero appears throughout the series of paintings at Riflemaker. We see him as a rider looking down from a rocky outcrop in a panoramic landscape reminiscent of Caspar David Friedrich. Wright cites the closing sequence of the early 1980s TV series ‘The Incredible Hulk’, with its attendant heart-wrenching 'lonely-man' theme, as a watershed moment that stirred deep sadness in him as a boy and taught him about existentialism and the human condition; the anti-hero returns to normal life, walking away from the camera with his head down and his essential solitude exposed. Although the paintings appear on first impression to be lighthearted as a result of the caricatured figures and bright colours, there is simultaneously a dark humour that permeates the work.

In this way the artist explores the boundaries between high and low art, some of his characters being painted onto kitsch thrift-store canvases bought in the US as he replicates that style in his own backgrounds. This exploration has extended beyond his own work. In 2009, he staged ‘Kunskog’ at 500 Dollars, Vyner Street, a space which he briefly co-ran. Wright selected one hundred works which embraced the gamut of contemporary drawing and the idiosyncrasies of taste, from works by Turner Prize winner Gillian Wearing, and established artists, Paul Noble, Michael Landy and Ged Quinn, to others who ‘draw in private’, including former subjects, John Hurt and David Thewlis. Stuart also invited ‘non-artists’ to submit work for the show, including friends, their children and his own mother. The final hang juxtaposed one of Gillian Wearing’s drawings with one by Australian entertainer Rolf Harris who also performed a number of songs at the private view (accompanied by Stuart on ukulele).

Stuart Pearson Wright won the BP Portrait Award 2001 for ‘Gallus Gallus With Still Life and Presidents’ or what the media dubbed the 'dead chicken' painting. In 2003 he shocked with a controversial naked portrait of Prince Philip.

The artist’s work features in numerous public collections including the British Museum, the Ashmolean Museum and the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum. Dinos Chapman, Kathy Burke, Deborah Warner, David Thewlis, JK Rowling, and Daniel Radcliffe are among the many fans and collectors of his work.

The exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue which included a transcribed conversation between Stuart Pearson Wright and the actor, novelist and director David Thewlis, an old friend and sometime collaborator of the artist (an image by Wright appears on the book cover of Thewlis’ novel, ‘The Late Hector Kipling’); a short story by Booker shortlist Adam Foulds and a short text by theatre director Deborah Warner. A number of Country and Western songs were also available on vinyl, which feature Stuart Pearson Wright singing and playing banjolelee/ukulele. (All three texts are below).

Written by Riflemaker and Stuart Pearson Wright.

STUART PEARSON WRIGHT

by Deborah Warner

He picks me up at Bethnal Green in a new, bright red transit van. Everything about him seems new. He’s engaged to be married, he’s talking excitedly about his discovery of Country and Western music, and behind the vibrant yellow roller door of his new studio, gleaming white walls are loaded with recent paintings.

Stuart Pearson Wright has been on a road trip to the States. Works with titles from the world of Country and Western – “I’ll Never Stop Lovin’ You”, “Rose Marie”, “Teardrops in my Heart”, “If we make it through December”, sing and dance from the walls. In the centre of it all, dominating this musical scene is a landscape of colossal size. At first you think you recognize the place, then you start to look closely, to really look. Is this the Grand Canyon? Is this a fantastical invention? Is this Breughel? Dali...? Is there an Escher-like trick in here? And the backgrounds to the portraits, where the artist and his muse pose as characters in Country and Western settings, who are they by? Stuart? No. Others? Amateurs? Just who painted these cliché-ridden backgrounds, these theatrical backdrops that audaciously co-exist with Stuart’s customary exquisite painting of face and hand? Where are we? Is this serious? Is this a joke? And just hold on, in the middle of it all there’s a film installation with Keira Knightley starring – no, not quite starring – “playing alongside” Stuart in a twelve-minute period drama short. What’s going on here?

Welcome to the world of Stuart Pearson Wright, New paintings, new departures, new frontiers and a new audacity to excite the mind. Everywhere tricks are being played with reality. He’s been here before, but he’s pushing frontiers like mad and it’s head turningly exciting.

In the same way as the playwright Samuel Beckett is doing something in the theatre with painting (in “Happy Days” the entrapped Winnie is embedded in a real landscape of earth and rock, whilst a vast trompe d’oeil landscape hanging behind her head seems to entomb her further), so Stuart Pearson Wright is doing something in painting with the theatre. He has long been fascinated by the theatre and by actors and acting. Now, in this new series, he puts himself as actor into the paintings and audaciously – I think brilliantly – borrows other painters’ landscapes as his frame. Many of the background works were found in junk shops and car boot sales. The canvasses have been meticulously cleaned, prepared and added to. Cliché-ridden backgrounds have become glorious springboards for invention. The naff is turned on its head, the poor landscape turned into a precious object. Even the original imperfections have been retained. Gloriously, in “Teardrops in your Heart”, the painting boasts an old canvas tear. In “Home on the Range” a space has been cleared for the “missing” ducks to swim on a patch of grey paint – a real/unreal pond to delight them through eternity. The mind turns, flips, and delights in the complex of reality on reality. Stuart exalts in these echoes. There is fun and there is great seriousness here, all combined. Beckett would have very much approved. So do I.

COWBOY AFTERNOONS

by Adam Foulds

Dismounted from their horses they stand as stiff as pitchforks and speak just as stiffly, in short phrases. They walk with a slow, swinging gait towards the camera and all of this says: Like this (like you), I’m out of my element which is wordless action on horseback under these enormous skies, amid gunfire, in the din of horses galloping through a canyon. Of course it makes them boring to listen to. Squinting out of their sunburn make-up they emit words reluctantly while doing other things, smoking, drinking, stirring beans, spitting with great precision, saddling horses, fighting in a bar, dragging a corpse by its heels.

Unless they’re in love. Love makes them garrulous (relatively speaking), makes them sing. They fall in love – or rather one of them does; they’re never all in love – with one of three women: a fair American who is spirited or delicate, a Mexican girl who is spirited, or an “Indian” who is probably spirited and certainly mysterious with a quiet inwardness that entices him. In reality they are all the same woman in different make-up and outfits, appearing in different films. Eventually the cowboy and the woman kiss, dryly, their faces pressed together with firmly closed mouths. The sexuality here has been – as my girlfriend once described the sexuality of Pre-Raphaelite art – pasteurised, raised to a terrible temperature in a tightly closed container and rendered safe. Nevertheless the kissing is a special thing as far as the film is concerned. Often it puts the sky in a different mood, of sunset or starlight.

The kisses are only ever an interlude or occur at the very end. To me they seem a kind of unnecessary garnish but as they pretty much always happen, they must be important.

All of it happens in a corner of the room on long, disagreeable afternoons, particularly when I’m off school ill, and only because there’s nothing better on and anything’s better than having the telly off. It happens while I’m lying on our sofa or sitting on the wilderness of fitted carpet. Outside the sky is drab with unbroken cloud that shifts slowly behind suburban aerials.

I don’t like these films. I don’t like the jammy colours of fifties Technicolor or the music, swooning strings, moseying guitars or lonely harmonicas. Horses are not interesting, certainly not compared to motorbikes. I don’t like the old-fashioned wood and leather world, agricultural at its edges, the historicalness. (I like the future, spaceships, holograms, cars that can talk). And, finally, I do not like the men who are the obsession of these films. The films stare at the men for hours, follow them as they gallop, crouch beside them as they shoot from behind a rock, listen to them singing a complete song from beginning to end, watch them as they briefly kiss. The films insist this is manhood in its best form and to be aspired to. But these men are like no men I know. These men almost never laugh. They kill people. They grimace constantly, experiencing little pleasure. They think by wiping sweat from their foreheads. They’re allowed to feel sad only when staring into the top of a tiny whisky glass. They’re always outdoors. They live in that vast, corny, implausible landscape. I’m pleased I’m not trapped out there, having to be one of them, so stiff and unreal, so manly. I can’t imagine what it must be like.

ONLY ELEPHANTS HAVE FOUR KNEES (Part One)

David Thewlis talks to Stuart Pearson Wright

SPW Hello? Ah you’re here. I’ll come and let you in [Sound of Roller shutter] Good to see you.

DT I’ve had a bit of a journey… Four cabs in a row wouldn’t take me. And then I got in one, and realised I’d forgotten my phone. [laughs]

SPW So you had to go back?

DT Yeah. Fuck! What’s going on there? [points to Long Time Gone] That’s different for you. Oh wow, these are brilliant.… It stinks of paint in here!

SPW All the pictures in the exhibition are named after Country and Western songs. Would you like something to drink?

DT Some wine please Stu.

SPW What’s going on with this cork? You pull it up and it doesn’t come out.

DT You might have to push it in with your thumb, which is gonna get messy.

SPW I bet this doesn’t happen in LA.

DT [Drinking] I’m not sure if the wine’s not corked, after all that. Unless it’s just that I’m not used to Pouilly Fuisse. Can it be corked when it's cork is rubber?

SPW That might just be the flavour.

DT So tell me what this is all about. It’s for the catalogue of your exhibition?

SPW Yes. Did you see the catalogue for Most People are Other People? [a previous exhibition] I did a similar thing with Timothy Spall.

DT …who lives beneath me. He’s got a leak and I think it’s my dishwasher that’s causing it. About five days ago he called, [in Timothy Spall voice] “Ello mate, it’s Tim here. I tell you what mate, I know I didn’t meet you for that Christmas drink but I got a leak and it seems to be coming from your apartment. I hate to be that kind of neighbour given our history over many years of working together but I’m ringing as a neighbour complaining that I’ve got a leak.”

SPW You think it might come from the dishwasher?

DT Yeah, he said: “it was really vibrating yesterday and leaking water” and I said “I didn’t put the dishwasher on yesterday, in fact I didn’t do anything yesterday”

SPW Nothing was vibrating in the flat?

DT No nothing was vibrating … apart from my head at one point. But then I pulled out the dishwasher, did my back in, crawled behind the dishwasher to have a look and indeed there is a big sort of damp patch and all kinds of stuff there.

SPW I know a good plumber.

DT Well I don’t think so much a plumber as a … a damp … I don’t know what they’re called.

SPW A Damp Man?

DT Yeah. A Damp Plumber. A plumber who specialises in dampness or a damp man who specialises in plumbing. But then I pulled the thing out, got in, wedged myself in and my back gave way. Couldn’t get out. I was in there like, “This would be a terrible death.”

SPW You couldn’t move backwards?

DT No.

SPW Don’t horses have that problem? They can’t move backwards.

DT Of course they can. I’ve been on a horse when they go backwards.

SPW Oh really?

DT Yeah, they quite often go backwards.

SPW Maybe I was thinking of…

DT I think you’re confusing horses with cows.

SPW Cows?

DT Cows can go upstairs but they can’t go downstairs. I’d hate to be the man who found that out the hard way.

SPW Yeah. [laughter]

DT But horses can go backwards. If they put them into a horsebox frontways they have to get them out backwards. Or vice versa. You’ve got it wrong there Stu. As an artist I’d expect you to know that: The dynamics of horses.

SPW I didn’t get round to that at the Slade. They didn’t discuss horses for some reason.

DT Maybe cows can’t go backwards.

SPW Maybe they can’t. Something can’t go backwards.

DT I suspect geckos… actually I think anything with legs can go backwards. Why shouldn’t they be able to? Maybe not elephants. They’re the only creature with four knees.

SPW Intriguing.

DT I think that’s right. And only pigs can sunburn. Anyway, what about Art? [laughter]

DT It’s Arizona isn’t it? [with reference to Long Time Gone]

SPW Well kind of. It’s partly Arizona and partly Utah…

DT Monument Valley’s the closest thing I would think to that. You ever been to Monument Valley?

SPW I have yeah, it played a large part in inspiring this series of paintings.

DT Yeah. But it’s not quite as alien looking as that, it’s like you’ve taken poetic license with Monument Valley.

SPW I have. I’ve turned it into a kind of Nob Land. Have you been to Bryce Canyon though?

DT Where’s that?

SPW That’s in Utah. Bryce does look as alien as this. Not that this looks specifically like Bryce but the nob-shapes are reminiscent of the place. There’s a person in it as well.

[extended silence]

DT Is that easy to spot?

SPW No, it’s like ‘Where’s Wally?’

DT Oh it’s that small is it?

SPW It’s ‘Where’s Stuart?’

DT Ok. Well that’ll give me something to do for the next half hour.

SPW Yeah. Let me know when you see him. I just finished it very recently, it took about 4 or 5 months.

DT How long does something like that take? [Referring to I’ll never stop Lovin’ you]

SPW I think that took about three or four weeks. I’m guessing now.

DT Why have you started painting on circular canvasses?

SPW I enjoy their kitsch value.

DT And should they be framed?

SPW I’m intending to frame the rectangular ones with driftwood, but framing a circular picture is a bit of a bugger…

DT Yeah.

SPW Cos you can’t get… well you can get round bits of wood of course: cross-sections. You could chop a tree down that was the same diameter as the canvas.

DT It would have to be exactly that diameter though.

SPW Yeah… Well I could go through a forest with a tape measure [they laugh] and measure them all… or get my people to do it. [more laughter]

DT I’ll come and join you on that. We’ll go through Windsor Great Park. There’s lots of fucking trees there…

DT So what’s the deal with cowboys? Why’ve you gone down the cowboy route?

SPW It comes from an interest in heroes and those male archetypes that we’re all supposed to emulate. Take James Bond: an archetypal male who, since he is played by different actors and has different scriptwriters and directors, subtly changes as a character through time. I’m interested in that process: the constantly shifting male ideal. Because I was born by artificial insemination and don’t know who my father is, I struggled at times to create a sexual identity for myself. I didn’t have a blueprint to follow, my father around, taking me up the park and playing football with me, and so on. That process of trying to work out how you’re supposed to function as a bloke in society, was a very self-conscious one, and probably still is, adopting different personas, trying to create an identity…

SPW I’ve landed on an aesthetic with these pictures, stuck somewhere around 1957 I think…

DT Right. I think it’s also quite an American aesthetic and an American kind of masculinity. I’ve noticed on American film crews you do tend to get much more hirsute guys, outdoor types, strong, masculine figures, whereas in Britain, they’re urban people. You get the idea that when the film finishes the American crew man will be out ranching cattle.

SPW I wonder if it’s anything to do with the size of the country and the fact that most of the country, by virtue of it’s size, is rural.

DT It is, and they’re descended from those pioneers who did ranch cattle. A neighbour of mine, his theory is that the Americans were the people who got on the Mayflower and emigrated, because they were optimistic, adventurous and had great pioneering spirit. All the people who were left behind were like: “that’s never gonna work is it" [laughter] “what do you wanna do that for?” so your English are more genetically disposed to cynicism: more damning of new enterprise. If there is a gene for enterprise and for ambition then that’s passed down into the American people. Americans are much prouder of their country. It’s an incredible land, and there’s nowhere comparable in England… “oh, but Cornwall’s quite nice. It’s quite rugged” [laughter] so we’ve got Cornwall and the Lake District, but there’s nowhere like that [points to Long Time Gone] there’s nowhere that’s other-planetary. I think that’s why Americans overuse the word awesome, because their land is awesome whereas Cornwall’s not.

SPW Cornwall’s very nice…

DT It’s lovely. I’m not knocking Cornwall.

SPW But it’s not awesome.

DT St Agnes is delightful.

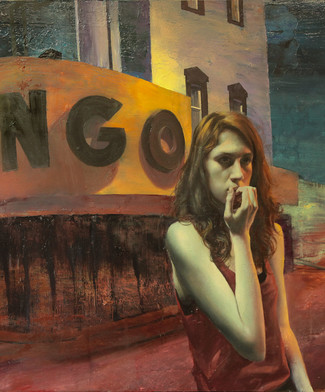

SPW So I took a road trip around Nevada and Utah and then went into Colorado and Arizona and New Mexico. It was only two weeks but I’ve been painting pictures ever since then, which are in some way set there. This one with the woman and a dog is called Rose Marie…

DT I love that one.

SPW Thank you. I actually bought that painting in a thrift store in Arizona.

DT What do you mean, you bought it?

SPW Well I bought that landscape without the woman and the dog and then…

DT So only the woman’s yours?

SPW Yeah, and the same with Home on the Range, the yellow-shirted fellow up there. I bought those two canvases in a thrift store and then brought them home and painted the figures into them. The ducks are mine as well. [in Home on the Range]

DT I suspected that.

SPW You see when I saw the original painting without the figure it made me think of the theatre. I love the theatre. I thought of it as a bare stage: a backdrop or empty space waiting for some sort of melodramatic moment to happen. The landscape wasn’t enough by itself. It needed to be inhabited by a character…

DT Do you have a story for what’s going on in Rose Marie?

SPW No. I found a picture on the internet of a woman in that pose, but with a Labrador. I couldn’t work out if she was screaming or laughing… I liked the ambiguity of the pose and the fact that the woman was holding the dog. That was the starting point for the painting.

DT It looks as though she’s in despair. If there was a house on fire behind her you’d understand it more. Maybe her house has collapsed under the snow.

SPW Well that’s the kind of narrative I get from it, but there isn’t a specific narrative that I’ve intended and that’s what I like about it. It’s open to interpretation.

DT And what have you done to this? [with reference to some thick impastoed lumps on Long Time Gone which he is viewing from one side] I’ve just noticed this in relief. There’s things stuck on that. What is that? like Chris Offili, mouse dung or something…

SPW Er no, but my house is full of mice at the moment, and mouse dung, which I should have collected together. I could have made a huge painting [laughter]. I could have sculpted a big cactus out of the mouse shit that I’ve got in my house and installed it in the gallery.

[big pause]

DT Do you mind me saying something about that one? [still with reference to Long Time Gone]

SPW No, go ahead.

DT There’s something in that section that doesn’t look finished… [He is referring to a bare patch that resembles a crater]

SPW Because it’s quite bare?

DT Because the rest of it is so textured and detailed.

SPW Before I painted any of the details I got big buckets full of paint and poured them all over the canvas, and then squished it all about and poured white spirit on top of it.

DT Right…

SPW And threw things at it and had a lot of fun.

DT So this is not based in any way on a specific photograph? It’s not like that’s a crater or something?

SPW That came about because when I left the white spirit on the canvas, if you imagine the painting flat on the floor, the weight of the canvas sagging created a kind of pool of white spirit there, and these lines leading into the pool are where the white spirit drained down and ate away the paint underneath. I liked the parallel with geological processes. It wasn’t something that I had made with my hand. It was like a mechanical or glacial process that I had no control over.

DT Ok.

SPW But then I always end up getting my little brushes out, that’s the problem.

DT The more I look at it… you joked about the nob element… actually there are fucking loads of nobs there. [laughter]

SPW There are.

DT …It’s a cross between turds and nobs. In fact you’ve got a title there. [laughter] not Where’s Wally? but Where’s Willy?

SPW Yeah, I did get carried away with a few of them. It was difficult not to… these trees are made of some kind of sponge from a modelshop. There’s a lot of texture in the painting. I used wax and mixed different kinds of minerals in, like marble dust.

DT Just seen that one [pointing at a particularly phallic rock structure in the painting]

SPW Some of them are disgusting. My dog Enid produces these stalagmite turds on occasion and every time she has, I’ve thought I must photograph it. I could’ve actually used those photographs as source material for this picture. A vertical turd would bear a close resemblance to one of these rock formations. Sadly I never had my camera on me at the right moment. I consider it a unique feat that Enid can do vertical turds. I’ve never seen another dog or person do them.

DT They’d remain standing up?

SPW Yeah, [laughter] just coming out of the ground.

DT Maybe if we shat squatting that would happen to us.

SPW Possibly.

DT If you were on a bad diet: Turkey Twizzlers

SPW Are you suggesting my dog has a bad diet?

DT I’m still looking for you in this painting. It’s a good picture to sit in front of to talk about because it becomes abstract: One of those images where you just start to see things. Now I’m starting to see people in there. This looks a bit like Richard Griffiths, a naked Richard Griffiths.

SPW Is that what he looks like in the flesh? Or are you speculating?

DT I’ve never seen him naked but I would imagine so.

SPW I’ll give you a little clue, the little self-portrait is wearing a red shirt.

DT We’ll find ‘im before the end of the night. Now I can see Rodin’s thinker here.

SPW I never saw that.

DT …with a couple more nobs around.

SPW Yeah, quite a few willies in there. But you understand it’s not about that. [laughter]

DT I think it’s my favourite picture you’ve made.

SPW Do you know there’s a Caspar David Friedrich painting of a bloke looking down across …

DT It’s on the cover of Nietzshe and stuff.

SPW …and books on Romantic painting. I was picking up on that idea of man encountering the landscape in all its vastness and strangeness. That might be a clue as to where the figure is. Rather than being in the landscape he’s regarding it from a vantage point.

[long pause]

DT I’ve just seen him! I’ve got him, ok. [laughter] I believe his horse is walking backwards.

SPW Yes it is! [laughter]

DT He’s exiting the painting.

SPW He’s had enough. He’s heading back to Cornwall.

DT That’s wonderful. I wouldn’t have seen it from here.

SPW Well hopefully it’s a painting that invites you to come quite close… I bloody hope so. I spent enough time painting it.

DT I really love it the more I look at it.

SPW Thank you. Did you see this one on the end? I’ve just finished this. [he refers to Teardrops in my Heart] I bought this landscape in a junk shop in Oslo and then painted the figures in.

DT How do you do it? Do you take a photograph? How do arrive at the pose? They’re all very anatomically correct. I mean down to the tiniest curl of the thumb and finger.

SPW I’ve been collecting images from books on films, Western films, and 1950s, ‘60s films.

DT But you’re in the picture so how do you …?

SPW I got a friend to take the photograph, but the pose was lifted from a film still, in this case from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, but something funny happened in the photo-shoot. In the original reference Vera Miles is holding James Stewart’s head and looking very sympathetic, and so in all the other photographs from the session Polly [Stuart’s fiancée and model] looks very sympathetic, but in this one she’s doing some strange sort of throwing her head back, ecstasy pose and … and so I chose this one as the one to work with, so it’s become something rather different from the original source. I thought it was wonderful that there’s something so incongruous about their expressions. It’s like he’s got toothache or erectile dysfunction.... [laughter] It’s not very clear what she is doing but it looks like she is enjoying something, which makes the picture quite perverse.

DT You’ve become increasingly good at painting yourself.

SPW Well I’ve done quite a lot of it.

DT And it’s getting increasingly photo-realist.

SPW Yeah. here’s the photograph that the painting was based on.

DT It’s pretty much to the absolute shadow. [comparing the painting with the photograph it is based upon]

SPW I think his left arm is a little bit too green. I’ve got to put in a little bit of red. I’ll glaze over bits just to tie the colours together.

DT And how do you do that? [train going past]

SPW Just put transparent paint over it.

DT That’s what I never understood about oil painting, oil glazes and…

SPW This particular paint is transparent so the light reflects on the white of the canvas underneath and comes through.

DT And is that done by thinning?

SPW Partly. Some pigments are naturally opaque and some are transparent. A glaze is just one transparent colour painted over another colour. In the pre-digital age you would have taken a photograph using a colour filter, glazing has the same effect, it just colours that part without obscuring the information underneath... I’ve got an etching as well. This is called, The Redskins is a Comin’.

DT Oh I’ve seen this before. That was the first time I realised you were going down the cowboy route. I love that, that’s fantastic.

SPW But not all the paintings in this exhibition are going to be specifically about cowboys. I’ve got this book called America’s Parklands, a National Geographic book printed in the early ’60s and it’s got these wonderful images. In the books from that period, you’ve got this beautiful quality to the printing, with those vivid colours.

DT Yeah.

SPW In one picture there’s a man showing a starfish to a little boy and a girl on a beach and the boy’s got a little sailor hat on… they are images that are somehow quintessentially American. There’s something so optimistic about them all.

DT Yeah.

SPW And because the book is about America’s parklands it’s all about tourists, and people experiencing the natural world. I guess that’s the link with Caspar David Friedrich and the Romantic tradition: the subtle shift from man experiencing a feeling of the sublime through nature, to man experiencing nature as a feelgood family experience from the back of his Station wagon.

DT You say you have recently been to America?

SPW Yeah.

DT Is it because you went to America you’ve decided to paint about America?

SPW Yeah, I guess so. That’s what led me into the landscape, and the landscape led me into the music and the music led me into the movies and that’s sort of how it came about.

DT When artists travel: Gaugin in Polynesia or recently Chris Offili’s in Trinidad, where you have a change of scenery: artists are inspired by, not just the light, but the tradition and the culture of a place. I always think that’s a healthier thing for a painter to do than for a writer to do…

SPW Why’s that?

DT P.G.Wodehouse said that writers should never let their books become a travel document just because the writer happened to have to go to that place, at that time, and then thought “oh, I’ll set part of the book here” though it was never part of the original plan. But I think for artists to do that is much more valid. When I was living in Los Angeles I was trying to write another book and suddenly all of my ideas were set in Los Angeles or were ideas about the American Dream or, be it, an Englishman living abroad.

SPW I think that’s quite an important point: the idea of the Englishman in America. It’s significant that these pictures are painted by an Englishman, not by an American. It means that they are very much a received idea of America, as seen through a number of different filters. I have taken one person’s ‘ideal America’, (in the form of a landscape painting from a thrift store) and then, in a sense, vandalised it, or colonised it with my own likeness: a lot of these are self-portraits. So I’m adopting personas or archetypes from American movies and inserting them in junk shops paintings.

DT You’ve taken a landscape and created something dramatic, by putting yourself in it.

SPW Stanley Spencer said that a landscape doesn’t really make much sense without a figure in it, and that a figure doesn’t make much sense without being in a landscape. Well from the point of view of a human, a landscape does make sense when there is a person in it because the person gives scale to the landscape.

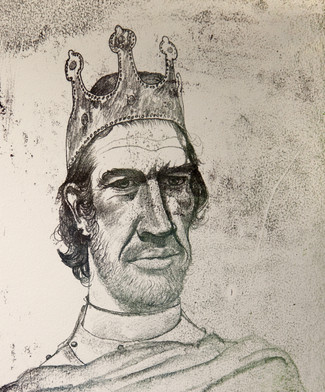

DT I’ve been looking at a lot of Elizabethan paintings recently cos of what I’m doing next, where the figure is against a blank backdrop, a character without a landscape…

SPW Are you going to be in an Elizabethan film?

DT Yeah, I’m going to play Lord Burley, That’s my first ruff. [They laugh]

SPW I should show you Maze and that might give you some inspiration. That’s set in the Elizabethan period.

DT In Mary Queen of Scots Burley was played by Trevor Howard.

SPW There’s Trevor Howard, up on the wall there. [Pointing at a drawing]

DT A very young version. When I saw him in Mary Queen of Scots he was just rather old and decrepid.

SPW Well, we all have to get that way eventually.

DT Yeah, well with my back I feel like I’m there today. Psychosomatically it’s preparing me for my next role: I have to play him like he’s 75. Well I age from 35 to 75, and all points in between.

SPW Will you have to grow a big beard?

DT No, they’ll stick one on. I could never grow one as fine as your Shackleton’s… You grow the finest beard.

SPW My cousin Jim has exactly the same beard growth. I’m just painting him and I together in this picture here [he points to Buddies in the Saddle]

DT It almost grows up to your lip.

SPW I think it’s because I cycle [They laugh] and it gets cold…

DT I’ve been on a bike.

SPW Did you see my pith helmet there? I’m going to do an explorer painting. I did a pith helmet painting once before actually, called Les Exotiques. When I was at the Paris flea market, I bought this little ‘African’ scene that was incredibly crudely painted. There was a group of ladies on the beach, and some palm trees. It was a kind of African paradise. So I painted a self portrait into the picture with a pith helmet, behind one of the palm trees wanking… [They laugh]

DT Of course you did.

SPW It was a comment on colonialism.

DT Spilling your seed?

SPW It was quite disgusting really.

DT So how many paintings are you doing?

SPW As many as I can, and I’m recording some Country and Western songs as a limited edition vinyl. They are going to be playing in the gallery space. A lot of them are Slim Whitman songs.

DT Ah,

SPW Do you like him?

DT He’s my Dad’s favourite. I think he had the entire collection of Slim Whitman, so growing up I was raised listening to Slim Whitman. Like Rose Marie, Indian Lovecall…

SPW That painting is called Rose Marie. It’s named after the song.

DT No way! My Dad would play them all the time. So Slim Whitman was the soundtrack to my youth.

SPW Well, I’ll have to make sure you get one of these records.

DT Yeah.

SPW Do you want to watch the film?

DT Yeah. That’ll be great.

[They watch Maze]

For Part Two of Only Elephants Have Four Knees visit the Maze project here.