Things Standing Still

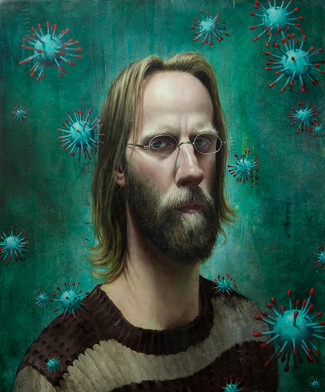

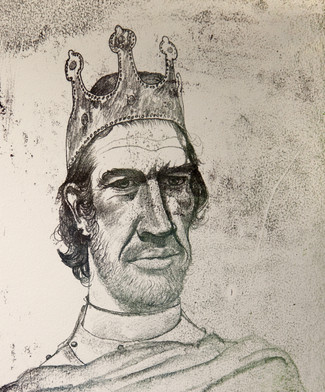

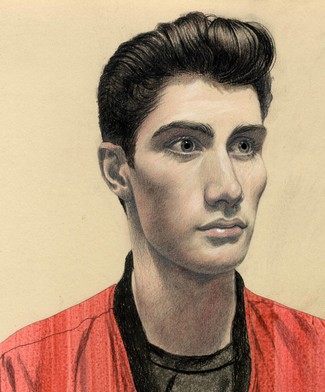

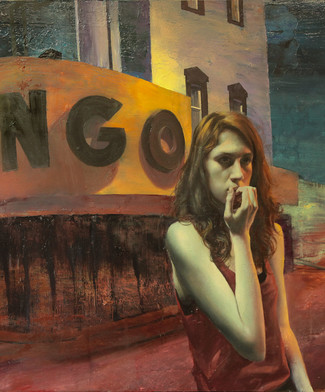

These paintings were first exhibited as part of Things Standing Still, an exhibition of work by Stuart Pearson Wright, James Lloyd and Jennifer McRae.

A SMALL COMPASS

by William Packer

Still Life, Nature Morte as the French have it: neither term is entirely unambiguous, satisfactory. At best there is a whiff of suspended animation to it, at worst death. Yet, whichever it is, we all know what it means, or think we do – the bowl of fruit; the glass of wine and loaf of bread; the vase of flowers. And it has been a part of painting since painting began – the lily in the Virgin’s hand; the bird pecking at her hem; the eggs on Martha’s table. The puzzle is only why it is such things speak so powerfully to us, even now. Perhaps, because their very familiarity, their essential, modest mundanity, gives them an immediacy that touches us directly, in our own experience, though the image may have been depicted centuries ago? Velasquez’s eggs are our eggs too.

Yet those very qualities of ordinariness served also, and for centuries indeed, to keep still life firmly in its place on the lowest rung in the hierarchy of art, as being in essence amoral, unconcerned with higher and spiritual values. Although, by the 17th century, in Spain and Holland especially, still life had at last become established as something more than the mere ornament of a narrative, distinct of itself and highly-collectable into the bargain, even Chardin in the 18th century still had to fight long and hard for the serious acceptance of his work within its disciplines. Only in the 19th century did the penny seem finally to drop, that simplicity and truth to nature were high enough values of themselves.

For it is a peculiar quality of still-life, that it returns the painter to an uncompromising engagement with first principles as a painter, rather than as an agent of some higher or narrative purposes. After all, quite how light, and space and material form are to be rendered in two dimensions on a plane surface is a puzzle that artists have faced since art began. And the strange thing is, so it seems to me, that the more concentrated and particular the focus, and minute the scrutiny, so the more imaginatively potent does the enquiry become. For here is the world, as it were, in the grain of a sand – the paradigm and parallel reality to the greater world, to be explored in the imagination and realised in the act of painting, if only in the attempt.

The three artists here, each now on early mid-career, have already established a substantial reputation as a painter of the figure and in particular the portrait – and how wonderfully they give the lie to the pernicious myth that figurative painting is a dying art, if not yet dead. Yet good painters of the figure are good painters perfectly capable of other things, and it is always a mistake to label them too closely to keep them in their box. These three, certainly, have always painted simply what intrigues them enough to want to paint it, whether quick or still.

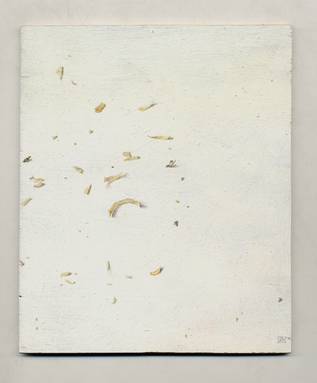

And, as painters of still life, each could indeed hardly address the particular object with a closer eye, each rendering it the more singular and remarkable by the isolation of its presentation on the canvas. Yet so closely complementary as they are in their work, so closely similar their preoccupations, and matching each other so closely in their technical command, they yet remain quite distinct in the actual performance.

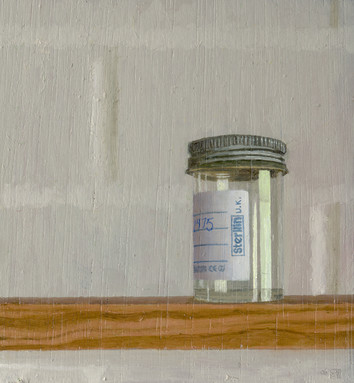

James Lloyd is perhaps the more straight-forward of them, with his eye for the casual formal studio incident – a yellow plastic bag crumpled in a corner; a discarded pair of rubber gloves; the workaday stool in the centre of the room; the empty trestle; an empty pot on an empty shelf. These are things seen just as they are for what they are. This is the world we too know directly by experience, that, here, we are invited to share.

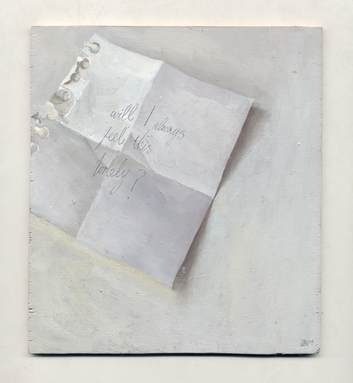

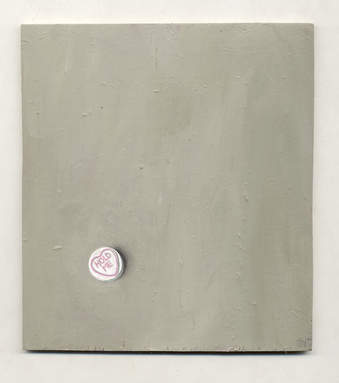

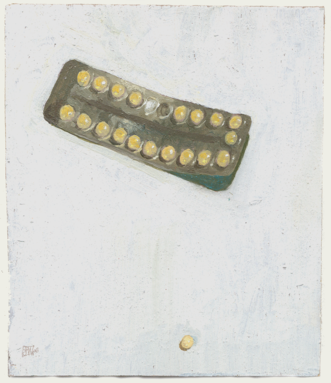

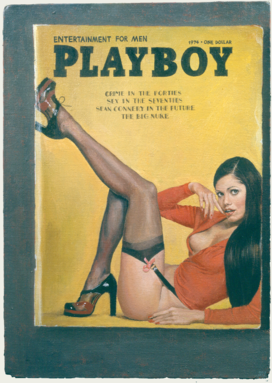

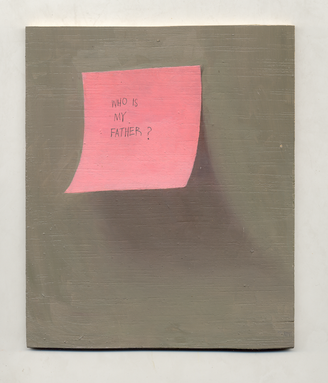

Both Jennifer McRae and Stuart Pearson Wright, thought apparently no less direct in their immediate approach – Miss McRae’s log kid gloves for example, her squeezed tubes of paint, her crumpled shirt: Wright’s yellow shoe, his folded scrap of paper, his eggs on toast – are, by contrast, the more metaphysical in the inferences they propose, how ever obliquely. She sets her objects against the purest, plainest ground. And by the allusive titles she gives them – Map for that spread-out shirt; Disquiet for those long grey gloves – she invites us to speculate on hidden and transitory life. He plays games that are formal, conceptual and ironical by turns. A Playboy Cover is at once nothing more than a painting of a sheet of printed paper, flat on flat, and so much more. That large black fly on the white board: is it dead yet, or as yet innocent of its fate? Do we take those nail-parings on the floor as a self-portrait? ‘Who is My Father?’ asks the pink post-it curling on the board.

Taking each in turn, this is fascinating and beautiful stuff.

London, June 2006